Small encyclopedia with Indian instruments

The text is taken from an excerpt of Suneera Kasliwal, Classical Musical Instruments, Delhi 2001

Santur

The santoor, an instrument recently adapted in Hindustani classical music, is among the most outstanding developments of this century. From the valley of Kashmir, an accompaniment to the Sufiana musique, it underwent a total transformation and emerged with a wider range of expressiveness and with features of a solo Instrument on the international concert scenario.

Prototypes of the santoor with similar or different names have also been in vogue for years in countries like China, Hungary, Romania, Greece, Iran, etc. The basis of the principle of sound production in the santoor was later applied to the making of the modern pianoforte in which the strings are struck by mechanical keys. The Indian version, i.e. santoor, is trapezoidal in shape and played with two wooden sticks.

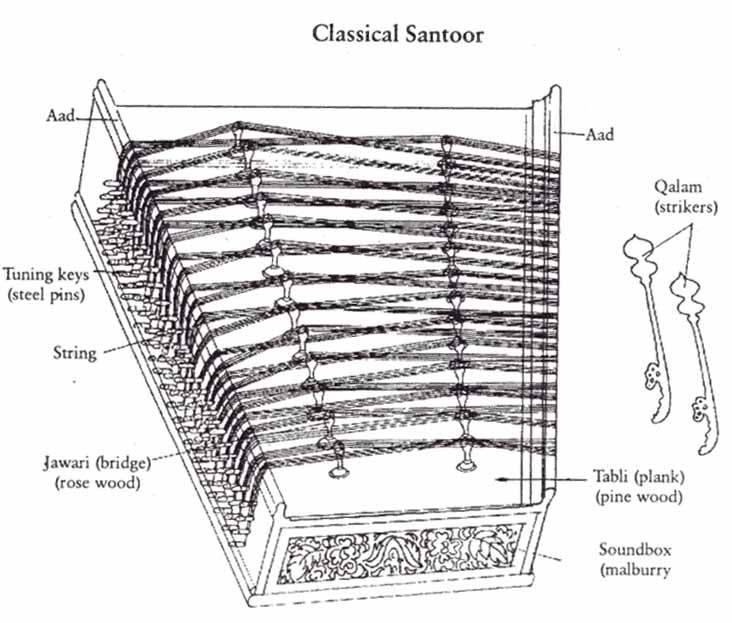

The santoor is a recently developed instrument. It was introduced into Hindustani classical music only about forty- five to fifty years ago. Thus the instrument is yet to be standardised. The length, width and height of the instrument, number of bridges, number of strings, their order and thickness, i.e. gauge, the sitting posture of the player, the playing techniques all of these vary from artist to artist. Although the basic structure remains the same, the santoor adapted in Hindustani classical music differs from the Sufiana santoor in many ways. If we start with the number of strings and the number of bridges, we would find that the number of strings varies between eighty to a hundred whereas the number of bridges have increased from twenty-five to twenty-nine, thirty-one and sometimes even forty-two, forty-three, thus varying the number of strings stretched on each bridge consequently. Some bridges have three strings and some have two. In the lower octave for the thick strings, some artists prefer one string to one bridge. The soundbox of the classical santoor is either made out of the wood of the mulberry tree, walnut or tun. The plank (of both sides) is made of pine wood or walnut or even of plywood. Sometimes it is a mixture of all these kinds. As a covering for the front, sometimes red cedar is also used. The bridges are made of rosewood and on the top portion of the bridges little pieces of ivory, stag horn or bone are fixed which act as jawari. This is done for the fine tone of the strings. Nowadays, plastic and metal are also used for jawari, but the best effect comes from ivory. Strings are put in the pins on one side and tied to the tuning pegs across the board. These pins and pegs are made of iron with chromium coating and tuned with the help of a hammer-shaped tuner. For strikers mostly walnut wood and rosewood are used. Sometimes strikers made of mulberry wood are also used. Strikers of classical santoor are heavier than those used for the Sufiana santoor, as heavier strikers help sustain the notes.

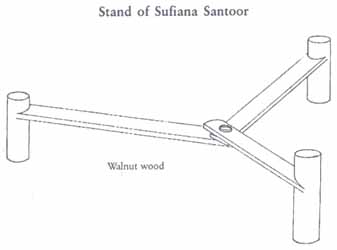

Most artists prefer to keep the Instrument in their laps instead of on the triangular wooden stand of the Sufiana santoor. Thus the resonance of the Instrument is reduced intentionally, which helps the player produce more precise note to note sound, especially while playing quick succession of the notes (tanas). With the times, the tonal quality of the classical santoor has improved immensely. The techniques used in presenting the whole performance patterns of the Ragdari System, i.e. alap, jod and gat, the portions of slow and fast tempos, have also developed a great deal.

The santoor is the only Indian classical Instrument which is struck. It is a staccato instrument and cannot lend to techniques such as meend, gamak and andolan, which are very characteristic of Indian classical music. The purists are not happy at the intrusion of this instrument into the traditional domain of classical music. Santoor players are quite aware of this criticism and to deal with this problem, i.e. the lack of continuity of sound, each and every artist has introduced something or the other in the Instrument and in its technique.

Some of the artists use accessories like the rod of the slide guitar, to facilitate production of effects of meend (glide) while playing alap mostly in the lower octave. Some of them use contact mikes in order to get a more sustained sound. A number of experiments with the wood, strings and with the size and weight of bridges and strikers have been carried out by the artists to get a better tonal quality and sustenance of sound from the santoor.