Small encyclopedia with Indian instruments

The text is taken from an excerpt of Suneera Kasliwal, Classical Musical Instruments, Delhi 2001

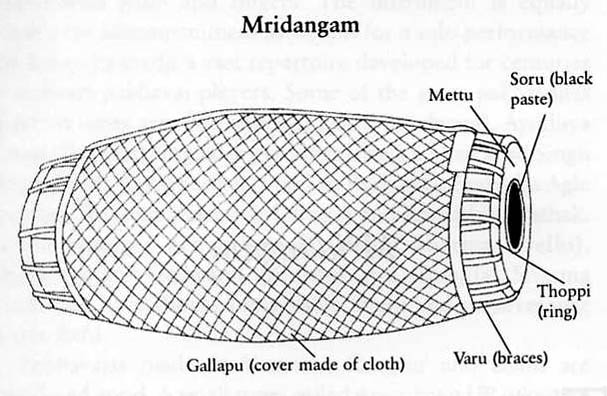

Mridangam

The classical drum of South Indian music is the mridangam. This is an indispensable accompaniment in the concerts of both the vocal and instrumental music in south India. It is also known by the name of maddal or maddalam.

The body of the mridangam is scooped out of a single block of wood. Jackwood or redwood is the ideal choice of mridangam makers, but the wood of morogosa tree or the core of the coconut tree and the palm tree is also used for this purpose. It is shaped like a barrel whose right head is a little smaller than the left. The instrument is one-and-a-half or two feet in length and its diameter is twenty-five to thirty centimetres. The making of the parchment is a highly developed skill. The right head of the drum consists of three concentric layers of the skin, the innermost being concealed from view, which is a complete skin, and two layers at the periphery. Out of these three the complete one is made of cow-hide with calf-skin used for the outer ring and sheep skin for the inner ring.

There is another version of the arrangement of the skin, i.e. the interior is made of calf skin, the middle layer is of goat skin and the outer thick layer is made from cow skin.

The left head consists of only two rings. The outer one is made of buffalo skin and the inner one is of sheep/goat skin. Both the parchments are stretched and kept intact by means of a plait called chattai or pinnal made of twisted leather straps. These two plaits are connected with the leather braces of buffalo/cow skin. These can be tightened or loosened to keep the instrument in tune. At times small pieces of wood are also put in between these braces, in order to switch over to the desired pitch of the instrument. The right head of the drum is loaded with a permanent fixture of black paste. The circular layer, called 'soru', is a composition of manganese dust, boiled rice and tamarind juice or a composition of fine iron fillings and boiled rice. Occasionally, a stone, called kittan, is powdered and mixed with rice in proper proportion. This black paste is applied on the inner skin in small grains and finely rubbed over for hardening with the polished surface of a hard stone. The paste is thickest in the centre and thins out towards the edges. It is this black paste which gives the fine characteristic tone to the mridangam. The left face is not loaded with black paste like the right face, but at the commencement of a concert, a paste of soojee (fine flour) and boiled rice mixed with water and ashes is temporarily fixed on to the centre of right head. The quantity of this paste is so adjusted that the note given by the left head is exactly an octave or a fourth below the note tuned at the right side.

The diameter of the left head is greater than that of the right head by about half an inch. The right head diameter varies from six-and-a-half inches to seven inches and the left head diameter from six-and-a-half inches to seven-and-a-half inches. The right head is tuned to the tone note of the main performer.

On the two hoops of the instrument, there are sixteen interspaces for the leather braces of buffalo skin to pass through. By downward and upward strokes with a small hammer on the hoop at appropriate points, the pitch of the instrument can be increased or decreased by as much as a full tone.

Even as a clever musician is able to display his creative skill in the field of music, as main performer, so also an expert mridangam player is able to display his powers of creative skill in the sphere of tala by playing new permutations and combinations of jatis. The cross-rhythmical accompaniment provided by the mridangam player is rather unique.

Mridangam and pakhavaj are the developed forms of the ankik portion of Bharat's Tripushkar, which was played horizontally. Therefore, both the drums have many things in common. But as they developed as parts of their respective systems, with centuries of growth they emerged as two very different musical instruments. Therefore, they tend to have similarities and differences on various aspects as follows:

Similarities:

- Both the drums are played in a horizontal position

- The art of making complex type of parchments in various layers for both the faces of drums in order to attain good tonal quality is equally developed in both the systems

- Black paste called 'syahi' in Hindi and 'soru' in Tamil, is used on the right face of both the drums

- Both the drums use the loading of wheat flour (sooji in the case of mridangam) on the left face just prior to the performance, which is very carefully scraped off after the performance.

- Both the drums are hollowed out of a block of wood

- Both the drums use small wooden blocks between the leather braces for tuning.

Difference between mridangam and pakhavaj:

- Mridangam is a little smaller in length than the pakhavaj. Mridangam is more barrel shaped, 'myrobolan* shaped, whereas the pakhavaj has an eccenteric bulge and is a 'barley shaped' drum, as prescribed in the Natya Shastra.

- The parchments (called pudi in Hindustani and muttu in Carnatic music) of both these instruments are different. The right face parchment of mridangam is prepared with three skin layers, whereas in pakhavaj both the faces bear the same two skin parchment. The peripheral skin of the right face in the pakhavaj is less wide than the mridangam.

- Though both the drums are loaded with dough paste on their left face, the quantity of dough used is almost double or twice as much for the pakhavaj.

- Both the drums use little wooden pieces to tighten the braces, but pakhavaj uses much bigger wooden pieces than mridangam called gatta. The wooden pieces used by mridangam are not thicker than the middle finger.

- Placement of both the hands on mridangam and pakhavaj differ, hence the mnemonics of mridangam and pakhavaj are also different.